© Robert McFarlane

American White Pelican

Pelecanus erythrorhynchos

Family: (Pelecanidae) Pelicans

Preferred Habitat: Coastal areas and large lakes.

Seasonal Occurrence: Abundant fall through spring. Uncommon in the summer.

Notes: With an impressive 9 foot wingspan, the American White Pelican is one of the largest birds in North America. Adult American White Pelicans are snowy white with black flight feathers visible only when the wings are spread. The massive beak is yellow-orange as are the legs and feet. During the breeding season, adults grow a horn on the upper mandible near the tip of the bill.

American White Pelicans migrate here for the winter from northern breeding grounds often travelling in large flocks, sometimes flying long distances in V-formations. Winter residents are common in the southern half of the state, especially along the coast and on inland reservoirs in the northern half and Trans-Pecos region.

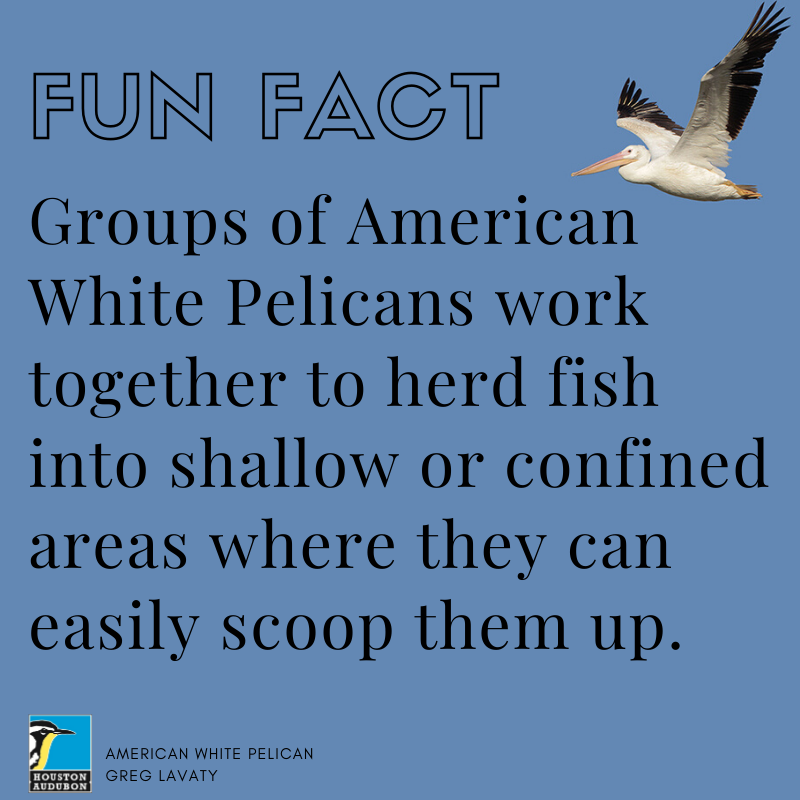

While the birds soar gracefully in the air, they are awkward on land. John James Audubon observed, "Clumsily do they rise on their columnar legs, and heavily waddle to the water. But now, how changed do they seem! Lightly do they float, as they marshal themselves, and extend their line, and now their broad paddle-like feet propel them onwards." American White Pelicans do not dive from the air for fish like Brown Pelicans; they forage by swimming on the surface, dipping their bills to scoop up fish, then raising their bills to drain water and swallow their prey. Groups of pelicans will feed cooperatively, working together to herd fish into the shallows for highly efficient, synchronized, bill-dipping feasts.

American White Pelicans can be found on coastal bays, inlets, estuaries, and sloughs where they can forage in shallow water and rest on exposed spots like sandbars. The Bolivar Flats Shorebird Sanctuary, Archbishop Joseph A. Fiorenza Park, and Arthur Storey Park are great places to observe these majestic birds this winter.

Profile by Carrie Chapin: One of the largest birds in North America, the American White Pelican is a sight to behold. With the second longest wingspan of birds in the U.S. after the California Condor, and its fascinating bill, they are difficult to miss. American White Pelicans can be identified by their large size, white plumage, black wingtips, yellow-orange bill, and visibly short neck in flight. The best time to see these birds near Houston is in the late fall and winter months after they return from breeding farther north. Interestingly, unlike many other fish-eating bird species, their population was not significantly impacted by the use of DDT. However, nesting site disturbance and habitat loss caused a decline in their population before the 1960s. Notably, the population has increased by over 3% per year since and is beginning to cause conflicts with the aquaculture industry.

American White Pelicans use both freshwater and saltwater areas to forage. The gular pouch on the lower jaw allows them to scoop up fish, crayfish, frogs, salamanders, and other small aquatic animals. Unlike Brown Pelicans who dive for their prey, American White Pelicans scoop prey from the water’s surface while swimming. They also use cooperative foraging techniques in small flocks to gather fish and make them easier to catch.

American White Pelicans breed along bodies of water in the north-central U.S. Breeding birds develop an epidermal plate on their upper jaw that is shed as soon as the eggs are laid. Pairs form shortly after flocks return to the breeding grounds. The female chooses the nest site, and both parents help form a shallow scrape, barely deep enough to keep the eggs from rolling. Exactly two eggs are laid two days apart and are incubated for 30 days by both parents. Interestingly, siblicide is the norm, and the larger chick always harasses the smaller chick. As a result, the smaller chick usually dies from starvation, unable to compete with its sibling. After three weeks in the nest, the surviving chick leaves to join a creche or pod of other chicks. This group is protected by only a few adults and allows the parents more time to forage. Young leave the nesting grounds with their parents at about eleven weeks of age.

These amazing birds can be seen soaring in flocks anywhere around High Island. Loafing groups are also a common sight at the Bolivar Flats Sanctuary. Keep your eyes peeled for these magnificent birds!

-

Cornell Lab of Ornithology

-

Field Guide

© Joanne Kamo

© Joanne Kamo

© Joanne Kamo

© Greg Lavaty, www.texastargetbirds.com

© Greg Lavaty, www.texastargetbirds.com

© Greg Lavaty, www.texastargetbirds.com

© Greg Lavaty, www.texastargetbirds.com